Three days per week, I get childcare. That’s three days to fit in all my work, all my appointments, all the grocery shopping for the past two and a half years of being highly risk-averse and not bringing the baby into indoor public places… Occasionally, I’ll get to squeeze in reading a book. For work or pleasure.

Of course, that’s when daycare is open. Three times since March of 2020, we’ve pulled our kids out of daycare for months at a time. I stopped work entirely when that happened. I am incredibly fortunate to be able to drop my work at a moment’s notice for an undetermined period of time and take care of my children. It is a curse to have to drop my work at a moment’s notice for an undetermined period of time and be a full-time stay-at-home parent, when I never wanted to be.

We are so lucky to be able to survive on my husband’s income. My work has always provided the financial extras: savings, paying down credit card debt… (When we originally made this plan over a decade ago, we assumed the recession would be over at some point, and the extras would be vacations. Our mistake.)

In late 2019, I wound down all my big projects. Return to the Enchanted Island was published in November of that year, when I was eight months pregnant. I sent out a bunch of pitches to a bunch of editors, and then signed off to take three months of maternity leave.

(You see where this is going, don’t you…)

I was one week away from restarting work when the first lockdown hit in 2020, and suddenly the 3.5-year-old was all over the 3-month-old and I was still nursing overnight and my husband never actually went back to the office and life has never been the same, although we at least got the silver lining of everyone else in the world understanding why we were struggling, because everyone else in the world was struggling in their own way to some degree. The publishing industry was decimated.

I haven’t gotten a book contract since.

All those pitches I sent out way back in 2019 are still being sent out. Plus more. I’ve done samples and reports of new books, and am actively pitching five different novels at the time of this writing. I’m even grateful, in a perverse way, that I haven’t gotten a book contract in the past couple of years, because I never really had guaranteed time or brainspace to tackle a full book.

Time feels different now. We all know this. A day with a young kid at home can feel eternal, and eternally boring when you’re stuck inside and have to constantly focus completely on a small child who will do dangerous things no matter how much you’ve childproofed your house but who is also preverbal and so has no way of giving your brain any interesting feedback and so it becomes boring in a weird way of fixed focus on a monotonous-seeming task of keeping a tiny human alive…and by the end of the day, there is no energy left in your brain to do anything, let alone the creative task of writing a sometimes traumatic story in a new language.

My brain is Swiss cheese, and words slip through those holes. Words in both languages.

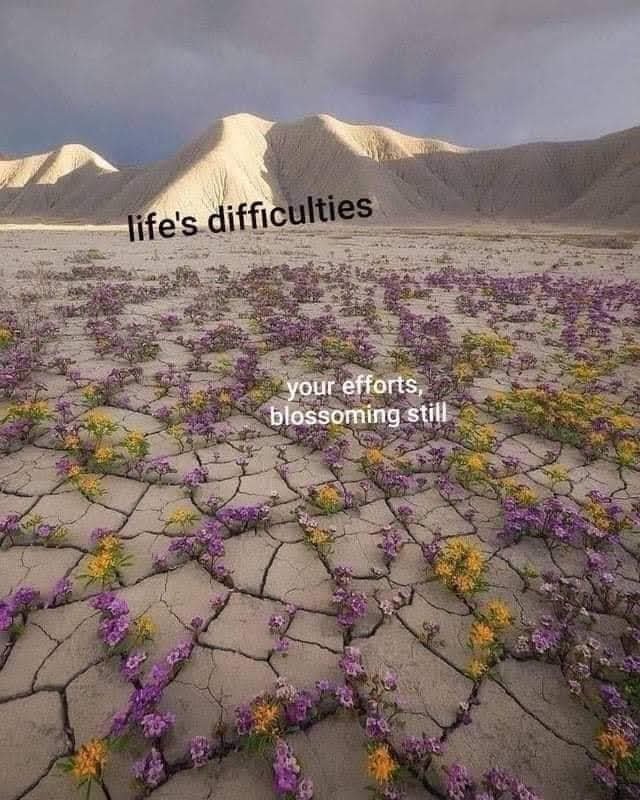

And yet.

Why despair, why fall into doom and gloom, when there are other ways of measuring success and fulfillment, when there are still new ways to spark creativity?

I may not have published a novel, but I have still published. I have still done the work of translation, and it has been shared with other people. I have done excerpts and stories and interviews, I have done panels and workshops, I have shared my knowledge. I have worked on approximately a billion graphic novels. And just last month, in the grand tradition of the flood that follows a drought, I got two new translations of some of my favorite authors’ work accepted in magazines in the same week! (Both are forthcoming in the fall.)

In those periods where even translation felt like too much, I sat and fiddled. I made a new website, got new pictures. Redid my bio and CV. Looked for new opportunities, researched magazines and publishers and residencies, made lists. All so I could be ready when the time was right.

And this time, the endless and strangely measured time that sometimes feels like such a curse, has born some unexpected fruits, the ones that can only grow given enough time. The endless days and nights of unfocused thoughts flitting aimlessly to nothing of import gave my synapses the chance to make new connections about old work: I’ve found a wholly new understanding of the novel I translated for my MA thesis in 2014 that had never found a home. I’ve scrapped and completely rewritten the reader’s report, and have started translating it anew. Amazing what eight years of growth and a little time with the front burner available for it can do.

Through it all, there is the balance that I always wanted for my life, of being present for and with my family, of being the first line of defense and comfort for my kids, of raising really good humans, while still being able to exercise my mental muscles in a vastly different creative way. Yes, I have fewer hours in the day/week/year to do work, but if the pace of my career is different than some of my colleagues because I have actively chosen to teach love and compassion to some new humans, I can be very satisfied at the worthiness of my life’s pursuits. All of them.

Of course, there is always that small part of my brain that looks at my translator friends with all their successes and prizes and published novels, and feels jealousy. Envy. Sometimes wholly despondent. But it is a much better choice to celebrate the wealth of wonderful art being produced by everyone, the laurels and crowns that will come to each of us in turn. (Plus, I’m on meds now for the anxiety and depression. It’s doing WONDERS.)

To borrow an image from my minister: These years have been, for my professional life, working quietly in the fertile darkness, like a daffodil snug in the fertile soil all winter, just waiting for the conditions to be right. Blossoms will come in their time.

It’s still hard. But I’m still here. We’re all still here.